(8-12 minute read)

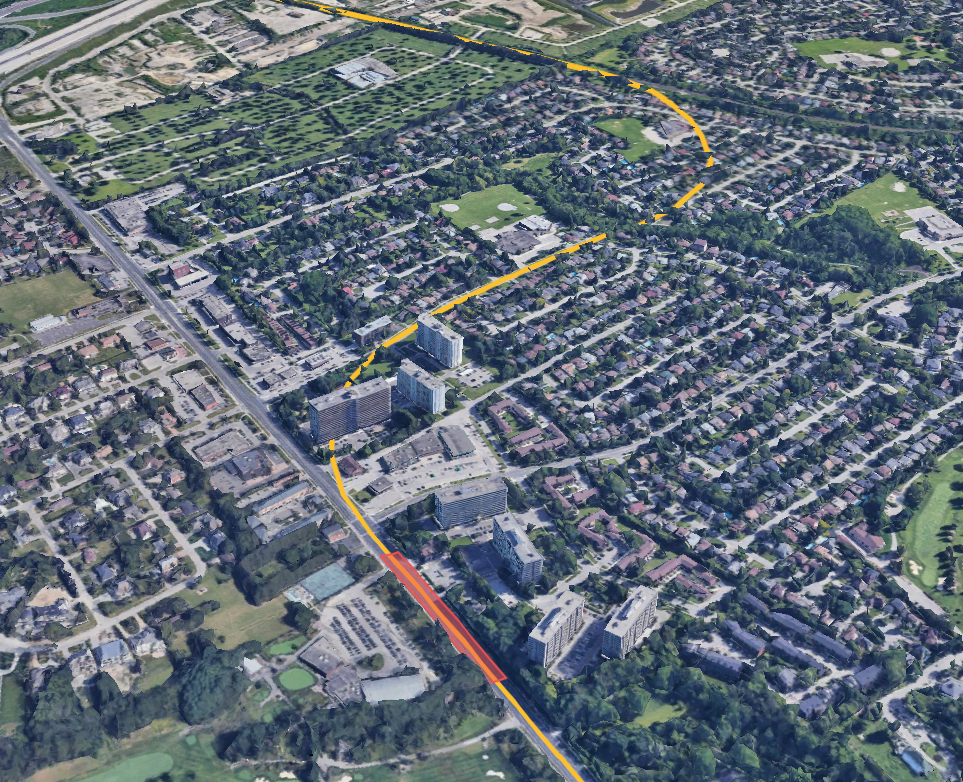

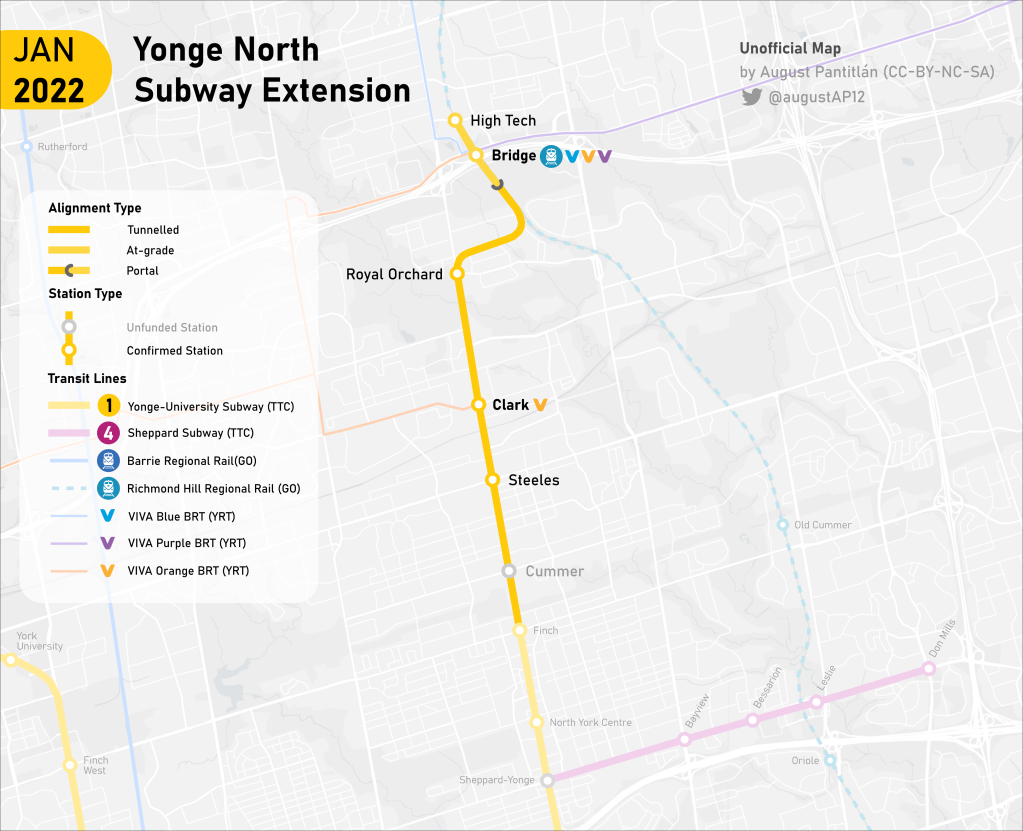

Image: The approximate alignment of the Yonge North Subway in Royal Orchard, including the area where a station is proposed

The existence of Royal Orchard is more prevalent than ever for any stakeholder involved in the Yonge North Subway project. The $5.6 billion proposal to construct a subway that passes through the suburban neighbourhood has spurred more headlines than any other event in Royal Orchard history. Unrelenting opposition from several residents have pushed Metrolinx to make various costly changes to this segment of the extension with little additional benefit. This article will cover the opposition’s emergence, address their platform, and review Metrolinx’s response.

Mounting Opposition

Several residents were alarmed with the new alignment of the Yonge North subway extension veering under Royal Orchard. You can read more about the YNSE project, alignment changes and the community’s reaction in meetings in my other article:

After the March update to the alignment, several community members organized as part of the Royal Orchard Ratepayers Association. They formed a group known as ‘Keep the Subway on Yonge‘, referring to Metrolinx’s original YNSE proposal – Option 1.

A Flawed Platform

‘Keep the Subway on Yonge’ makes 4 primary claims against the current YNSE iteration:

- The proposal “adversely affects the health and well-being of thousands of residents“

- Homes will be ‘blighted’ financially if a subway line is constructed beneath them

- No rationale to tunnel under through the “heart of a single-family neighbourhood”

- No guarantee by Metrolinx to ensure that noise and vibration mitigation techniques will be effective

The group closes their position by stating that the YNSE proposal would “devastate” their neighbourhood and would be a “very costly mistake”.

Now, let’s address each of these points based on the information given by Metrolinx, independent studies, and the outcomes of past subway projects to discuss why these points are invalid.

Health of Residents

Modern subway operations do not adversely impact health of those living nearby – although construction processes can cause temporary impacts related to noise and air quality.

Notably, there will be no intrusive top-down construction within the neighbourhood, aside from low-impact drilling as part of geotechnical investigations. As such, construction dust (that is detrimental to respiratory function) will not be an issue in Royal Orchard.

Contrary to the belief of some residents, improvements to public transit actually have the benefit of promoting healthy, active living and better environments. The YNSE is expected to offset 4.8 kilotonnes of yearly GHG emissions, improving air quality in the region. This is the equivalent of 1,000 cars used over the course of a year (assuming 4.8 tonnes of GHG per car per year, per the EPA).

While many Royal Orchard residents support a fully below-grade alignment, a higher proportion of above-grade segments would improve the health of daily commuters by reducing their exposure to air pollution. A study in the journal of Environmental Science & Technology found that commuter exposure to PM2.5 has a positive relation with distance to above-grade portions, as well as depth. This means that deeper and more extensive underground transit lines are more conducive to the accumulation of particulate matter, to the detriment of commuters’ health. This is one benefit of Option 3’s above-grade segments. Contrarily, the deeper Royal Orchard Station in the current iteration would negatively affect air quality for riders.

Furthermore, increased public transit use is correlated with higher rates of physical activity. A Queen’s University paper found that commuters who took public transit recorded 80 minutes/week of physical activity while commuting, while those who drove/carpooled only recorded 30 minutes/week.

Public transit infrastructure incentivizes transit-oriented development around station areas, which in turn promotes active transportation. Transit-oriented communities are better suited by design to walking and cycling rather than driving – a benefit to the physical health of residents.

All of this, in fact, is great for the health of current and future Royal Orchard residents.

Financial Impact on Property

Before diving into this concern, note that property values should seldom be a priority in rapid transit planning. The goal of public transit is not to boost the value of one’s house, but to increase mobility and accessibility in an equitable and sustainable manner.

Regardless, homes near rapid transit tend to see an increase in property values in nearly all circumstances.

According to a 2018 study by Concordia University, single-family homes (SFH) that are less than 800 metres from a Toronto subway station are 10.9% more expensive than those 800-1600 metres away, and 16.9% more expensive than homes over 1600 metres away (p. 60). On average, SFH listing price and distance from a subway station are inversely correlated, with prices decreasing by 0.004% for every additional metre from a station. The difference is even greater for denser housing forms.

The simple prospect of a future Royal Orchard station on the line would have led to higher values by speculation of future development. Now, with the confirmation of a Royal Orchard station, any concerns about the loss of property values are completely void.

Rationale of Tunnelling

The most direct path between Yonge Street and the CN/GO rail corridor results in an alignment under Royal Orchard. The primary goal of this shift is not only to minimize tunnelling, but also to minimize the resources spent on underground stations. By remaining on Yonge, the proposed station in the Langstaff area would be underground – the new alignment avoids this expense. Underground stations are the greatest single contributor to infrastructure cost on rapid transit lines, and any opportunity to bring transit at-grade or above-grade should be considered (providing displacement and environmental damage is minimal, which it is in this case).

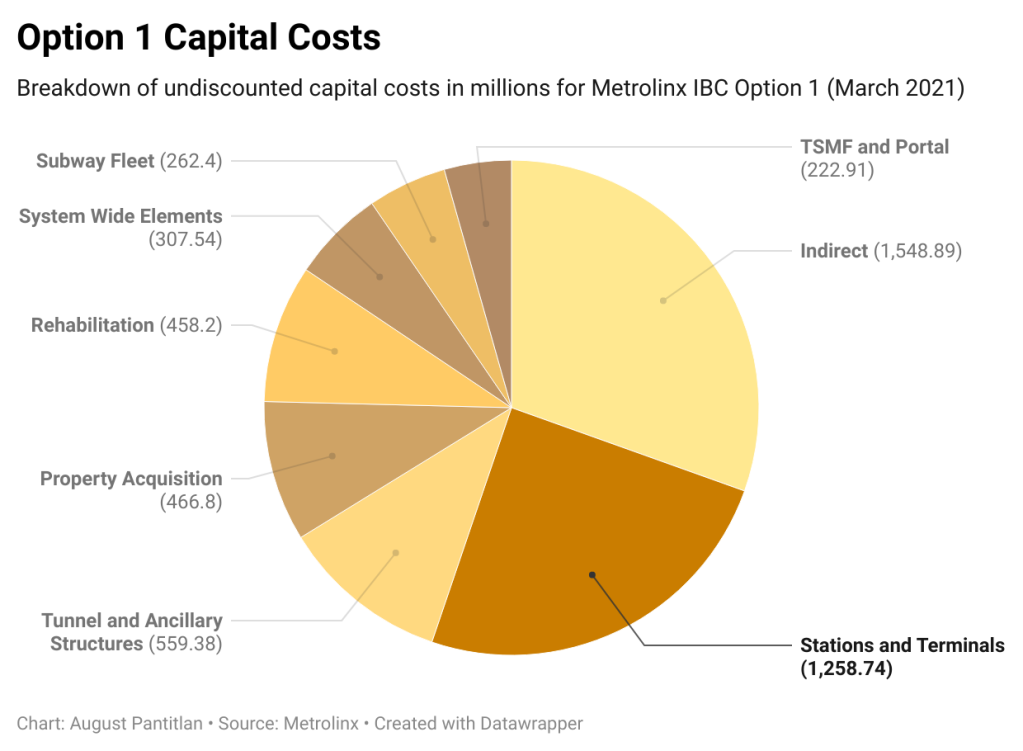

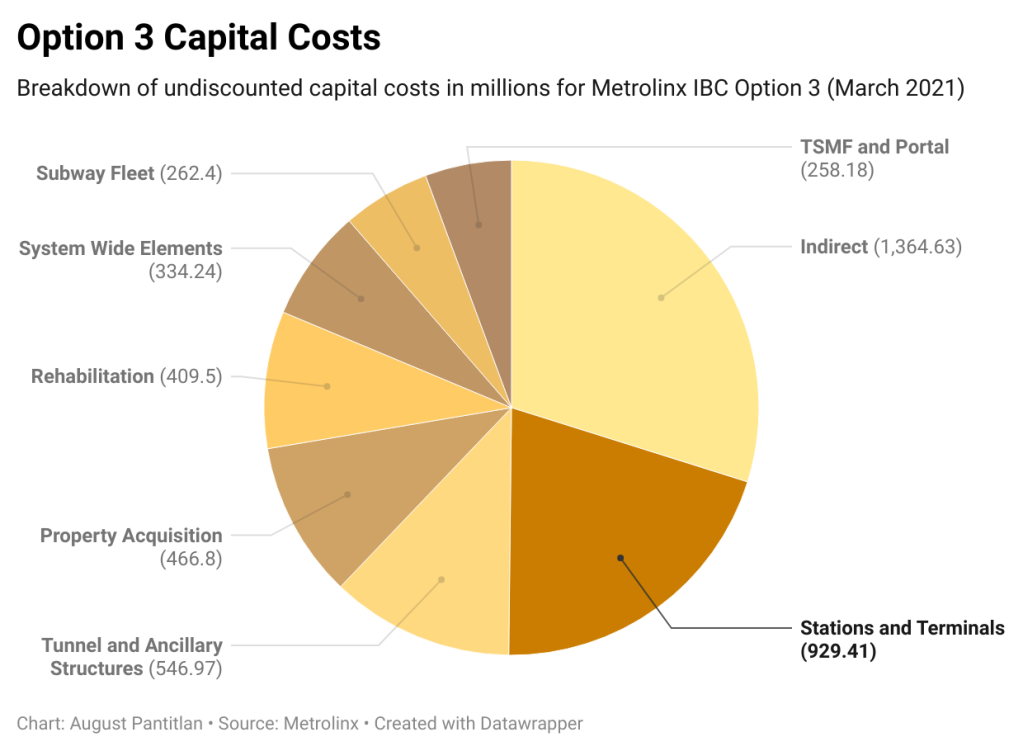

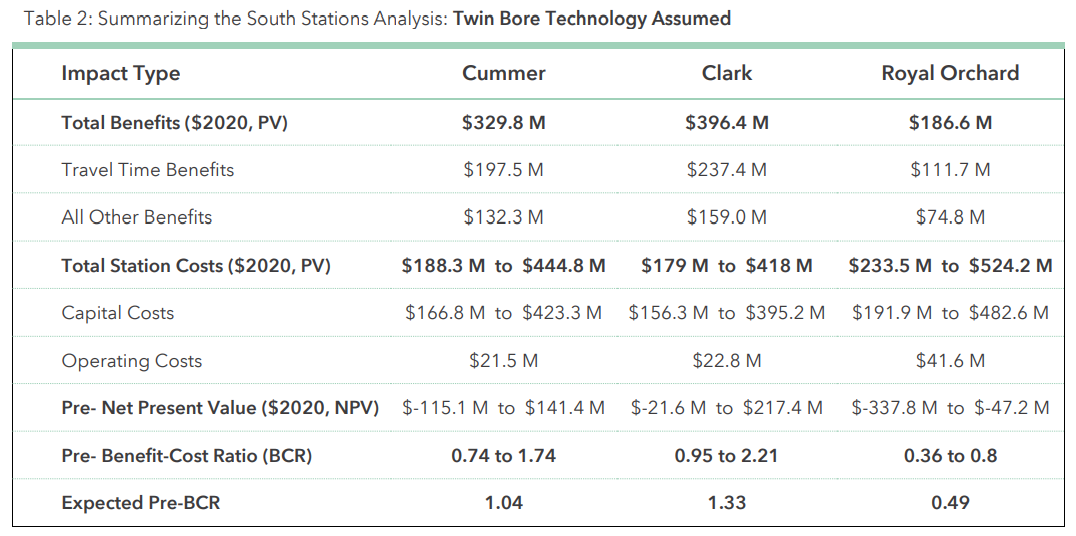

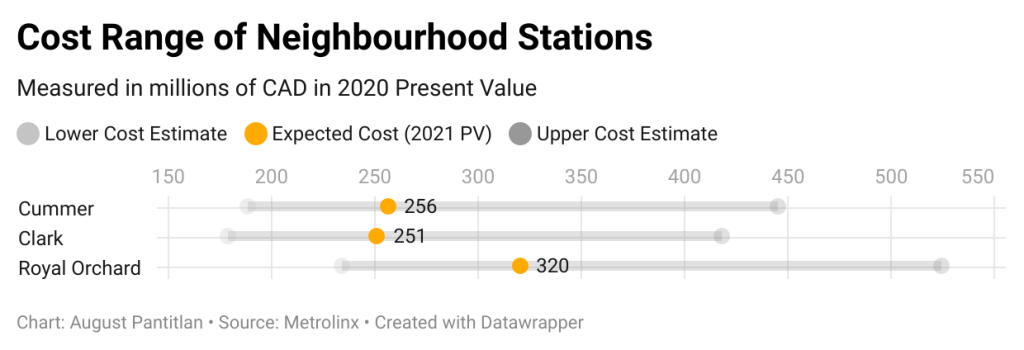

The following charts show a breakdown of costs between the fully tunnelled Option 1 (endorsed by ‘Keep the Subway on Yonge’) and the preferred Option 3 with only the three core stations included. Option 1 station capital costs were $330 million higher than that of Option 3, according to Metrolinx. Considering that an additional neighbourhood station costs $400-$500 million, it is then obvious that Metrolinx prefers Option 3. The amount saved on the new alignment corresponds to more funding for an additional station.

Note that these estimations are based on net present value, and the funding required is higher.

Both transit and community activists have advocated to shift the S-style curve north through the industrial zone around the Langstaff-Bridge area. Aside from other issues, costs will increase dramatically in this scenario if Metrolinx pursues a tunnel-bored option.

Interestingly, the Royal Orchard group advocates to move the tunnel from beneath their neighbourhood and instead place it under another – the future high-density neighbourhood at Langstaff-Bridge. In any scenario, the subway would still be tunnelled under homes, just not homes in Royal Orchard. Hence, supporters of ‘Keep the Subway on Yonge’ inadvertently admit their entitlement by declaring a subway tunnel under their neighbourhood as ‘unacceptable’, while dictating that the subway should instead go under another neighbourhood.

Noise and Vibrations

Metrolinx has consistently maintained the position that noise and vibrations will be imperceptible at surface level while the subway operates beneath Royal Orchard. A few skeptical community meeting attendees could not understand the word ‘imperceptible’ and required multiple explanations. For convenience, here is Merriam-Webster’s definition:

Imperceptible

- (adj.): not perceptible by a sense or by the mind: extremely slight, gradual or subtle

Metrolinx’s position is supported by a recent sound test conducted at a York University lecture hall, directly above the Line 1 extension to Vaughan (TYSSE). At this location, the track bed is approximately 20 metres below the surface. The test concluded that noise produced by the subway is “practically imperceptible”. An image from the article depicts a 28.7 decibel measurement. For comparison, a faint whisper averages 30 decibels!

Thus, built-in noise mitigation is proven to be effective. Many of the TYSSE’s design solutions are adopted into the YNSE project – ensuring noise and vibration is kept to a minimum.

Considering that tunnels beneath Royal Orchard will be 36-50 metres below the surface in the proposal’s latest iteration, any concerns of noise should be dismissed.

And no, one’s house will not collapse or suffer structural damage from the faint vibrations of a subway operating over 36 metres below. This has not happened in Toronto before, despite many areas where the subway operates at a shallow depth beneath old neighbourhoods.

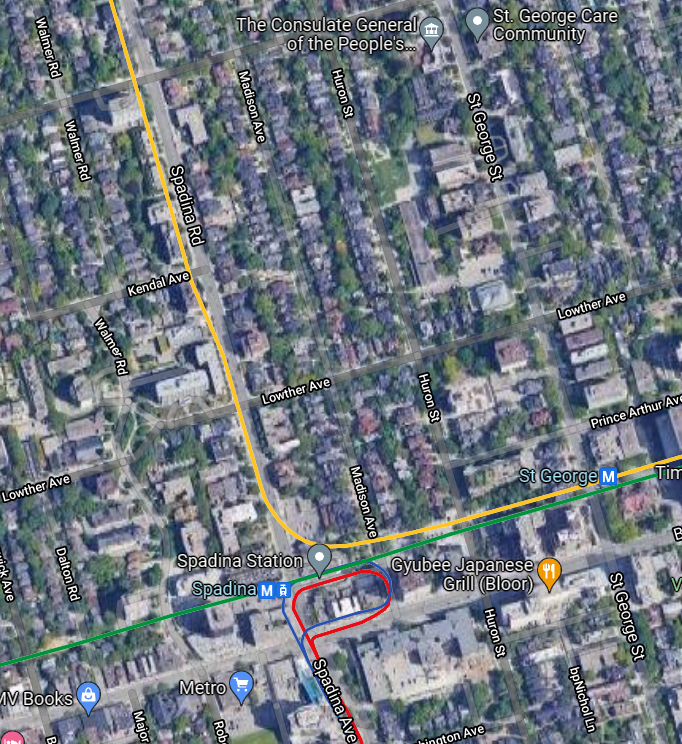

The Annex is a prime example of an established Toronto neighbourhood that is crisscrossed by shallow subway lines. Unsurprisingly, the character and standard of living has not been destroyed by the subway’s existence. Instead, the subway is a convenient and vital service that increases accessibility, supports businesses, encourages growth, and improves the overall quality of life in the area.

An Ironic Ratepayers Association

Keep the Subway on Yonge was formed by the Royal Orchard Ratepayers Association (RORA). In Canada, these associations primarily serve two purposes:

- Advocate for prudent public spending to minimize tax burdens

- Represent the collective interests of most homeowners

The irony of RORA is that it supports a plan that spends excessive public funds to construct a less economical public project. Clearly, the organization is ignorant of public spending, as it pushes for very costly and unnecessary adjustments.

Instead, they prioritize the flawed interests of a number of vocal homeowners. There is a tendency for many homeowners to have an irrational fear of change within their communities and the devaluation of their property. The solution, for many, is to oppose any development, even that which is necessary for the betterment of the city and region. This type of opposition is unsustainable and has zero benefit to society.

Royal Orchard Station

Amid stiff opposition, officials confirmed that Royal Orchard station would be built – as if the increased depth of tunnels were not enough.

Increasing Costs

Per the initial business case from March, Royal Orchard was estimated to be constructed 40-45 metres below grade – the deepest station on the TTC network. By comparison, the existing TYSSE and Line 4 stations were generally built at a depth of 20-25 metres. Among in-development projects, Avenue Station on Line 5 will be 32 metres deep; Line 2’s Lawrence East Station will be around 40 metres deep. Unfortunately, due to the change in alignment in December, Royal Orchard Station is now up to 50 metres below grade.

The station will require a sequential excavation approach (mined, similar to Avenue Station on Line 5) whereas the better-performing Clark and Cummer stations can be constructed efficiently by the cut-and-cover method at depths less than 20 metres.

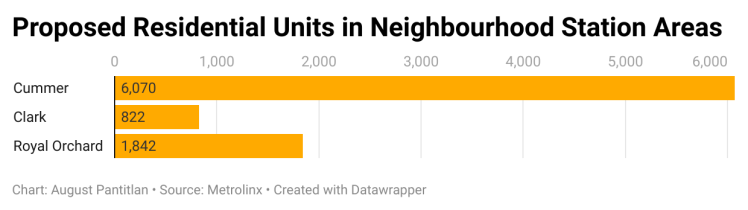

The depth and complexity of Royal Orchard Station does not bode well with the already poor benefit-cost ratio prior to the increased depth. It is expected that costs will be $400-$500 million per neighbourhood station, with Royal Orchard being the most expensive – recent changes could increase its cost beyond $500 million.

Note that costs are measured in Present Value (PV), and do not reflect the true funding necessary for each station. This value would be closer to the upper cost estimate.

Ridership and Catchment

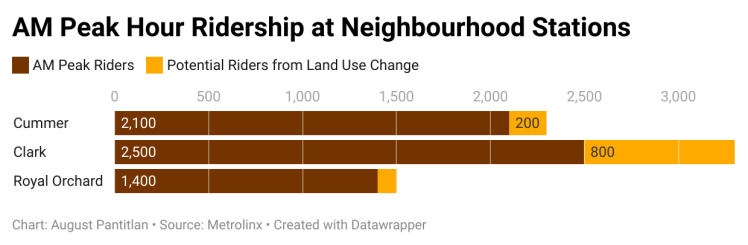

The recent iteration depicts the station further south from the centre of the neighbourhood than previously planned. Station catchment figures have not been updated since this iteration, but it can be speculated that the projected population and employment within walking distance of the station has decreased (and thus projected patronage). Metrolinx previously estimated Royal Orchard’s morning peak hour ridership at just 1,400.

A more recent addendum by Metrolinx evaluated ridership across the entire line with each additional neighbourhood station (accounting for overlap in station catchment). This study found similar AM peak ridership overall for the YNSE with the addition of either Royal Orchard or Cummer.

However, the ridership performance of the stations and the entire extension cannot be evaluated based on peak-hour ridership only. Ridership patterns during peak-hours do not reflect the ridership throughout the day, and this is an important factor as an increasing number of transit trips are taken outside of peak hours. The denser built form and greater employment expected in the Cummer area is more predisposed to significant off-peak transit use. Comparatively, Royal Orchard’s lower density and scale would perform less impressively.

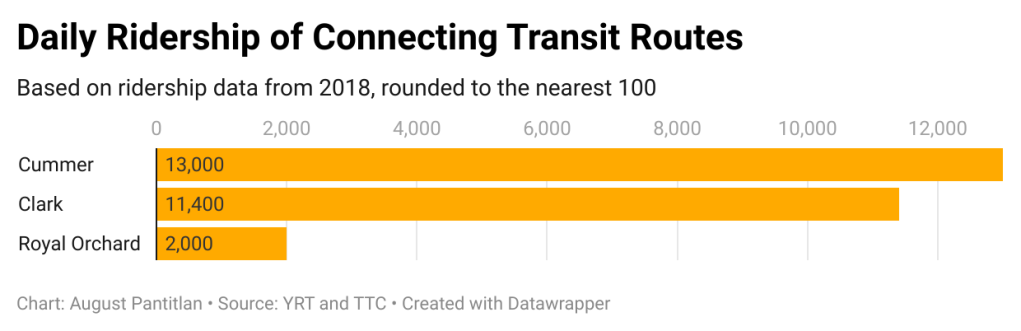

The case for Royal Orchard is weakened further by poor local transit connections – only YRT Route 3 serves the area. Ridership of connecting local transit lines in Royal Orchard is far below either Cummer or Clark stations.

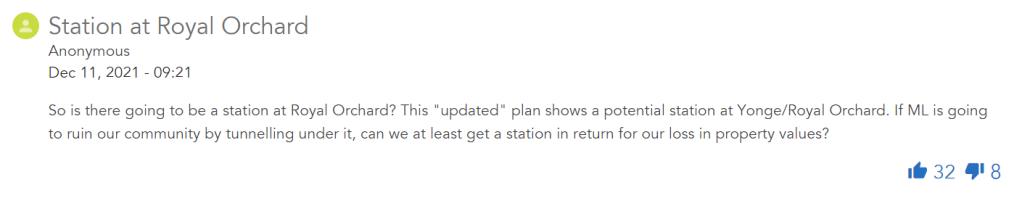

The Opposition’s View

A recent Toronto Star article shows that ‘Keep the Subway on Yonge’ is still opposed to the YNSE tunnel beneath their neighbourhood regardless of whether or not a station is built. The few members of the group that supported a station, primarily did so on the grounds of reparations for the tunnel. Here is a well-received question from a virtual community meeting:

It is interesting to note that most of the opposition, despite their supposed ‘support for transit’, are more concerned with falling property values (a myth) than the long-term future of their community and surrounding region.

The Verdict

Metrolinx’s addition of Royal Orchard station is not sensible in its current form. This is the worst performing yet costliest neighbourhood station. The demands of a few hundred concerned locals have directly caused refinements that diminish the benefits of a more centralized and shallow station in Royal Orchard.

Despite Cummer Station outperforming Royal Orchard Station, Royal Orchard was selected as the fifth station. Clearly, Metrolinx has prioritized one neighbourhood’s vocal minority above sound transit planning.

The Big Picture

A Bad Precendent

When Metrolinx panders to Royal Orchard’s opposition by increasing the depth and complexity of infrastructure, it sets a bad precedent for other projects in the region. For example, some Leslieville residents are pushing to move the Ontario Line underground in their neighbourhood, despite the readily available rail corridor. A Leslieville resident may consider:

If additional costs could be incurred to accommodate Royal Orchard’s demands, why not place more resources in Leslieville to bury the Ontario Line?

If transit planning is done in this manner, regional transit projects would suffer cost blowouts and need to be reduced in scope. This necessitates the removal of stations, shortening of lines, or cancellation of some projects entirely. The region cannot afford to maintain the largest transit expansion in its history and pander to local opposition groups simultaneously.

A Final Note to Opposition Groups

Opposition groups in places like Royal Orchard should consider how the world is changing around them and how their community must adapt. Even on a regional scale, some issues are prevalent:

- The Toronto area has been long underserved by rapid transit, and hundreds of thousands of less privileged commuters spend several hours per day in crowded buses, trains and streetcars

- The fastest growing urban area in North America desperately needs housing, and much of it needs to be supported by sustainable transportation

- The world is facing a climate crisis, and urban areas like Toronto need to address the impact of excessive automobile use through policy and infrastructure

- Amid rising construction costs, all levels of government must optimize their resources to build as much sustainable infrastructure across the region

Projects like the YNSE are part of the solution.

With further optimizations, such projects can provide greater benefit at a reasonable cost. The ability to deliver essential transit projects across the region is threatened when NIMBYs (Not-In-My-Backyard) oppose these optimizations over minor inconveniences and demand an unreasonable amount of resources to mitigate them. Onlookers, residents and city councillors should consider:

Are we willing to threaten the benefits of the project over the minor inconveniences required to make progress?

Should a few hundred property owners speak over the hundreds of thousands of people who would benefit from this project?

Ultimately, neighbourhood groups need to recognize that the best way to ‘save’ their communities is to take a step back, and look at the big picture.

Resources

- YNSE Initial Business Case, from Metrolinx

- YNSE Neighbourhood Station Analysis, from Metrolinx

- YNSE IBC Option 3 Refinement, from Metrolinx

- Metro Commuter Exposures to Particulate Air Pollution and PM2.5-

Associated Elements in Three Canadian Cities: The Urban

Transportation Exposure Study, from Environmental Science & Technology Journal

- Impacts of public transit improvements on ridership, and implications for physical activity, in a low-density Canadian city, from School of Urban and Regional Planning at Queen’s University

- The Effects of Urban Rail Rapid Transit Station Types on Housing Prices

in Toronto and Vancouver, Canada, from Department of Geography, Planning and Environment at Concordia University

- University lecture hall becomes testing lab for noise levels on Yonge North Subway Extension, from Metrolinx

- YRT Ridership, 2018